The Russian Revolution was a cataclysmic event that reshaped not only Russia but the entire geopolitical landscape of the 20th century. The roots of the revolution stretch deep into the failures of the Tsarist regime, which for centuries had clung to autocratic power while much of Europe surged forward into modernization and reform. The reigns of Tsar Alexander II, his son Alexander III, and finally Nicholas II, set the stage for the downfall of an empire. Through repression, political mismanagement, and missed opportunities for reform, the Tsars sowed the seeds of revolt. From the ill-fated assassination of Alexander II to the rise of figures like Lenin and Stalin, and the scandal surrounding Rasputin’s influence, the final years of Tsarism were marked by instability, and ultimately, revolution. This article takes a deep dive into these crucial moments that laid the groundwork for the rise of communism in Russia and the fall of its centuries-old monarchy.

A Glimpse into 19th Century Russia

In the 19th century, Russia remained largely an agrarian, feudal society, with the majority of the population living in rural poverty under a rigid and unyielding social structure. This period was marked by a massive gap between the elite and the working class, with the aristocracy enjoying immense wealth, privileges, and power, while the vast majority of the people struggled for basic sustenance. At the heart of this system was the Tsar, the autocratic ruler who held absolute power over the entire nation. Unlike in Western Europe, where political revolutions were beginning to take root and societies were transitioning toward more democratic forms of governance, Russia was lagging far behind.

The agrarian economy in Russia was heavily dependent on serfdom. Serfs were essentially bound to the land they worked on, belonging to the landowners. They were treated as property, unable to leave or seek better opportunities elsewhere, with little legal recourse against mistreatment. This made them comparable to slaves in many respects, as they had few rights and were subjected to brutal working conditions. The majority of these serfs worked the land on behalf of wealthy landlords, while the nobility and the ruling class enjoyed extravagant lifestyles, far removed from the struggles of the common people. This vast inequality led to a simmering resentment that would grow over the decades.

At the same time, Europe was undergoing an industrial revolution that transformed its economies, making them more dynamic and prosperous. While Britain, France, and Germany were rapidly industrializing, Russia remained largely a rural and agricultural country, with little emphasis on modernizing its economy or social systems. The rest of Europe was seeing the rise of middle-class society, political reforms, and the expansion of human rights, while Russia’s autocratic monarchy was determined to maintain the status quo. This isolation from the modernizing world would lead to further disillusionment among the Russian people, as they watched neighboring countries progress while they were stuck in the past.

The stagnation in Russia was exacerbated by a political system that refused to consider change. The Tsar and the nobility had little interest in granting any form of political or civil rights to the population, as doing so would have undermined their absolute authority. In fact, the Tsarist government actively suppressed any calls for reform or modernization, using secret police and military force to quash dissent. The Russian Orthodox Church also played a key role in maintaining the Tsar’s power, as it legitimized the autocracy and suppressed alternative political ideologies. While the rest of Europe was exploring new ideas of liberty, democracy, and equality, Russia remained stuck in a feudal past, with no clear path forward.

Despite the harsh conditions for the majority of the population, Russia was an enormous empire, with a wealth of resources. This paradox – a vast and resource-rich country dominated by a feudal system – contributed to the frustrations of the Russian people, who saw the potential for prosperity and advancement, yet were held back by an archaic political structure that favored the aristocracy and the monarchy. The gap between the elite and the common folk, combined with the lack of political reform, laid the groundwork for the revolutionary movements that would arise in the coming decades.

Tsar Alexander II: The Reformer Who Wasn’t

Tsar Alexander II ascended the throne in 1855, at a time when Russia’s isolation from the rest of Europe had become glaringly apparent. The Crimean War (1853-1856) had been a humiliating defeat for Russia, exposing the weaknesses of the Russian military and the country’s underdeveloped infrastructure. The war showed Russia’s inability to compete with the more modern, industrialized nations of the West, and it became clear that change was necessary for the survival of the empire. Faced with this reality, Alexander II embarked on a series of reforms that he believed would modernize Russia and bring it in line with Western Europe.

The most significant of these reforms was the Emancipation Edict of 1861, which freed the serfs. This was a bold and unprecedented move, one that was hailed by reformers and liberal thinkers as a step toward a more modern and equitable Russia. The serfs, who made up around 80% of Russia’s population, had long been trapped in a system of bonded labor, with few rights and no opportunity to improve their lives. The Emancipation Edict promised them freedom, allowing them to own property and marry without their landlord’s permission. It seemed like a watershed moment in Russian history.

However, the reality of the Emancipation was far less transformative than it appeared on paper. While the serfs were legally freed, the conditions under which they were “freed” were harsh and restrictive. Most peasants were not given land directly, but instead were allotted land that had to be paid for over a period of years. This debt, along with the high interest rates, left the majority of freed serfs in financial bondage. Many peasants were also forced to remain in their villages, as the land they received was often insufficient to support them. Without the tools, education, or resources to succeed on their own, most serfs found themselves in a situation just as desperate as before.

Moreover, the emancipation did not address the broader issues of poverty and inequality in Russian society. While some landowners were compensated for the loss of their serfs, the peasantry received little in return for their newfound “freedom.” The reforms did not include any real political or economic rights, and the old feudal system was replaced by a new form of semi-feudalism. For many, the Emancipation only deepened their sense of frustration, as they saw that the promises of liberty and equality had not materialized.

Alexander II’s failure to fully address the economic and social problems of the serfs was compounded by his reluctance to implement more comprehensive reforms. While he enacted some legal changes, such as reforms to the judicial system and military, he did not address the need for a more democratic government or the expansion of civil rights. His attempts at reform were, at best, superficial, and they failed to address the underlying issues of autocracy, inequality, and political repression that were rampant in Russia.

The lack of significant change during Alexander II’s reign set the stage for growing disillusionment among Russia’s intellectuals, liberal reformers, and working classes. Although Alexander II was regarded as a reformer, his inability to implement true systemic change alienated many and led to the rise of more radical movements. The discontent that simmered during his reign would eventually boil over into calls for revolutionary action, and Alexander II’s assassination in 1881 by a revolutionary group highlighted the deep dissatisfaction with the Tsarist regime. The assassin’s bomb marked the beginning of a new phase in Russian history, one that would ultimately lead to the overthrow of the monarchy.

Alexander II’s reforms, while well-intentioned, were ineffective and ultimately failed to modernize Russia in any meaningful way. His reign was a period of missed opportunities, and his inability to address the deeper structural issues of Russian society paved the way for the more repressive reign of his son, Alexander III, and set the stage for the eventual collapse of the Tsarist regime.

The Assassination of Tsar Alexander II

The assassination of Tsar Alexander II on March 13, 1881, was a pivotal moment in Russian history. It represented the culmination of growing dissatisfaction with his reign, particularly among radical reformers and revolutionaries who felt that the Tsar had not gone far enough in modernizing Russia. While Alexander II had introduced some reforms, such as the emancipation of the serfs, he had failed to address the deep structural inequalities in Russian society, leaving many of the masses still trapped in poverty and oppression.

The assassin, a member of a revolutionary group called the People’s Will, was part of a growing movement of radical intellectuals and activists who believed that only violence could bring about meaningful change in Russia. The People’s Will believed that the Tsar’s reforms were insufficient and that the monarchy itself needed to be dismantled in order to pave the way for a more just and equitable society. They saw Alexander II’s failure to push for deeper, more systemic reforms as an insurmountable barrier to progress, and they believed that his death would send a message to the Russian elite that the people’s anger could no longer be ignored.

Alexander II’s assassination was a shock to the Russian public, though it should not have been entirely unexpected. The Tsar had been the target of multiple assassination attempts during his reign, and his policies of gradual reform had only deepened the divisions within Russian society. His assassination highlighted the growing radicalization of Russian politics and marked a dramatic turn toward more violent forms of political activism. The people who opposed the Tsar saw no other way to force change but through direct action.

In the immediate aftermath of the assassination, the Russian government cracked down on political dissent, and revolutionary movements were brutally repressed. The Tsarist regime, in an attempt to restore order, placed blame for the assassination on all radical and reformist groups, further marginalizing those who had been advocating for peaceful reform. The People’s Will and other radical factions were hunted down, and many of their leaders were executed. However, the assassination also sparked a wave of political unrest, as it exposed the vulnerability of the Tsarist regime and the inability of the ruling class to address the deep-rooted issues of inequality and injustice.

While Alexander II’s death was a victory for radical revolutionaries in the short term, it ultimately led to greater repression under his successor, Tsar Alexander III. The new Tsar sought to restore the power of the monarchy by implementing more authoritarian measures, but in doing so, he alienated large sections of Russian society. The assassination of Alexander II set the stage for the more repressive and autocratic rule of his son, whose policies would prove disastrous for the stability of the Russian Empire.

The event also marked a turning point in the history of Russian political thought. The assassination and the subsequent crackdown on dissent inspired a new wave of revolutionary ideology, with thinkers and activists such as Vladimir Lenin beginning to formulate ideas about the need for a complete transformation of Russian society. While Alexander II’s assassination was a moment of triumph for radical factions, it ultimately signaled the failure of moderate reformism and the rise of more extreme, revolutionary ideologies.

Tsar Alexander III: The Repressor

Tsar Alexander III’s reign (1881-1894) represented a stark contrast to that of his father, Alexander II. Following his father’s assassination, Alexander III took a hardline approach to governance, adopting a policy of repression in response to the growing political unrest in Russia. Where Alexander II had been a reformer, Alexander III was determined to restore the autocracy to its full power, rejecting the idea of liberal reform and emphasizing control, stability, and order above all else.

Alexander III’s policies of repression were driven by his deep belief in the divine right of the Tsar and his conviction that any challenge to the monarchy’s authority would lead to the collapse of the Russian Empire. He saw his father’s reforms as a weakness, a betrayal of the traditional power of the Tsar, and he was determined to undo them. His reign marked a period of intense censorship, political purges, and state-sponsored repression aimed at quelling any opposition to the Tsarist system.

One of the most notable features of Alexander III’s rule was the introduction of the policy of Russification, which sought to impose Russian culture and language on the diverse ethnic and religious minorities within the empire. Non-Russian populations, including Jews, Poles, Ukrainians, and Finns, were subjected to harsh measures aimed at assimilating them into Russian culture. This policy sought to suppress local languages, traditions, and religions, often by force. It not only alienated the minority populations but also stoked ethnic tensions within the empire, leading to unrest and rebellion in various parts of the country.

Alexander III also strengthened the secret police, most notably the Okhrana, a political police force that operated with near-total impunity. The Okhrana was tasked with rooting out any form of dissent against the Tsarist regime, including political dissidents, revolutionaries, and intellectuals. The agency used methods of surveillance, intimidation, and brutal tactics to suppress opposition, and its reach extended into every corner of Russian society. The Okhrana’s effectiveness in crushing dissent reinforced the autocracy’s grip on power but also led to widespread fear and mistrust among the population.

In addition to political repression, Alexander III’s economic policies were aimed at consolidating the power of the aristocracy and maintaining the status quo. While some progress was made in industrialization during his reign, the focus was largely on preserving the old feudal system rather than promoting broad-based economic development. The working class, particularly in the rapidly growing industrial centers, faced harsh working conditions, low wages, and little legal protection. Workers had few rights and were often subject to the whims of factory owners and local authorities.

Alexander III also took a conservative stance on foreign policy, emphasizing the importance of maintaining Russia’s traditional role as a great power while avoiding entanglements in foreign conflicts. His foreign policy was focused on strengthening Russia’s influence in Europe and Asia, but it was also driven by a desire to project an image of Russian strength and stability. This focus on militarization, however, did little to address the underlying social and economic problems facing the country.

While Alexander III’s policies were successful in maintaining order and preserving the autocratic system in the short term, they sowed the seeds of future discontent. The repression, ethnic intolerance, and failure to address the needs of the working class created deep fractures in Russian society. The Tsar’s refusal to consider political reform or engage with the growing demands for change made him increasingly unpopular, and his reign would ultimately be seen as a time of missed opportunities for Russia.

In many ways, Alexander III’s reign set the stage for the eventual downfall of the Tsarist regime. His insistence on maintaining an autocratic system at the expense of reform alienated large segments of Russian society and created the conditions for revolutionary movements to gain traction. By the time of his death in 1894, Russia was a country on the brink of change, with widespread social unrest, growing political movements, and the seeds of revolution already being sown. Alexander III’s repression might have preserved the monarchy for a time, but it also paved the way for its eventual destruction.

The Timid Tsar Nicholas II

When Nicholas II ascended to the Russian throne in 1894, the empire was in turmoil. His father, Alexander III, had implemented a policy of rigid autocracy, suppressing any form of political dissent. While the Tsarist regime had held firm under Alexander III, Nicholas II inherited a Russia that was not only politically unstable but also beginning to show the cracks of economic discontent. The country was lagging behind Europe in terms of industrialization, and social movements were gaining momentum, both for greater freedoms and the rights of workers. Yet, Nicholas II was woefully unprepared for the challenges of ruling such a vast and diverse empire.

From the outset of his reign, it was apparent that Nicholas lacked the strength of character and political acumen needed to manage the complexities of ruling Russia. Unlike his predecessors, Nicholas was not a strong, determined ruler, nor did he possess a deep understanding of political affairs. He was, by all accounts, a deeply insecure man, prone to self-doubt, and often unsure of his decisions. His own admission of inadequacy was telling: “I know nothing of the business of ruling, and I am not yet ready to be Tsar.” This public expression of uncertainty did little to instill confidence in either the Russian elite or the masses, and it quickly became clear that Nicholas was not the decisive leader Russia needed.

Rather than addressing the economic and political issues facing his country, Nicholas preferred to remain detached from the day-to-day struggles of his people. He was more interested in his personal life and hobbies than in the urgent need for reform. His primary concern seemed to be maintaining the imperial family’s grandeur and engaging in luxurious pastimes, while the majority of Russians suffered under harsh conditions. This detachment from the issues of state was glaringly apparent when, during his coronation celebrations, an ill-conceived promise of free pretzels and beer led to a stampede that killed nearly 1,500 people in Moscow. Instead of taking responsibility for the disaster, Nicholas simply moved on with his diplomatic engagements, a move that further alienated the public.

Moreover, Nicholas’s lack of understanding of the political dynamics within Russia led to increasingly poor decision-making. He failed to recognize the growing demand for political reform and the need for modernization within the empire. While other European nations were embracing liberal reforms, constitutionalism, and the expansion of civil rights, Russia remained entrenched in its autocratic system. Nicholas clung to the notion of divine right, believing that he was chosen by God to rule, yet he failed to understand the evolving political landscape. He stubbornly rejected calls for a constitutional monarchy or democratic reforms, fearing that such changes would undermine his absolute authority.

Nicholas’s failure to modernize Russia or to address the growing demands for reform left him increasingly isolated from his people and led to mounting discontent across the empire. This detachment from the needs of the nation created a void that would be filled by radical ideas, including Marxism and socialism. Although Nicholas was not opposed to change in principle, he was unwilling to take the necessary steps to enact reforms that could have alleviated some of the growing social pressures. His reign, therefore, was marked by an inability to adapt to the changing political climate, and his failure to act decisively would ultimately lead to the unraveling of the Tsarist regime.

The 1905 Revolution: Rising Unrest

By the time the 1905 revolution began to take shape, Russia was on the edge of a precipice. A variety of factors contributed to the growing unrest that spread across the empire, culminating in a series of strikes, protests, and uprisings. The dissatisfaction with Tsar Nicholas II’s rule was widespread, and it was no longer confined to a small group of intellectuals or political radicals. The working class, peasants, and even some segments of the middle class were beginning to demand significant changes to the political and social order.

The immediate catalyst for the 1905 revolution was the tragic events of Bloody Sunday. On January 9, 1905, a peaceful march organized by Father Georgy Gapon, an Orthodox priest, took place in St. Petersburg. The protesters were seeking to present a petition to the Tsar, asking for improvements in working conditions, political freedoms, and economic reforms. They wanted to present their grievances in a respectful manner, hoping that the Tsar would listen to their demands. However, when the marchers reached the Winter Palace, they were met with gunfire. Imperial soldiers opened fire on the unarmed protesters, killing around 200 people and injuring many more. This massacre became a symbol of the Tsarist regime’s brutality and indifference to the suffering of its people.

The bloodshed of Bloody Sunday shocked the Russian public and led to widespread outrage. The event served as a wake-up call to many, showing the lengths to which the Tsarist regime would go to suppress even peaceful protests. The Tsar’s refusal to address the issues raised by the protestors, combined with his failure to take responsibility for the violence, further eroded his legitimacy in the eyes of the people. The massacre was not an isolated event; it was part of a broader pattern of government repression and incompetence that had characterized Nicholas II’s rule.

In the aftermath of Bloody Sunday, strikes erupted across Russia, and workers began organizing to demand better working conditions, higher wages, and greater political rights. The growing sense of discontent was not limited to the cities; rural areas, too, were rife with unrest. Peasants, who had long been burdened by poverty and a lack of land, began to demand land reforms, while liberal intellectuals called for constitutional changes and the establishment of a more democratic political system. These diverse groups, united in their dissatisfaction with the Tsarist regime, created a volatile mix of political movements that threatened the stability of the empire.

In response to the growing unrest, Nicholas II was forced to make some concessions. He issued the October Manifesto in 1905, which promised the establishment of a Duma, a legislative assembly with the power to approve laws. This was a significant concession, as it marked the first time in Russian history that the Tsar had agreed to share some of his power with a representative body. However, the Duma was a far cry from a true democratic institution. The Tsar retained the power to dissolve the Duma at will, and the reforms promised by the manifesto were never fully implemented.

While the October Manifesto temporarily quelled some of the unrest, it failed to address the deeper issues of inequality, political repression, and the lack of meaningful representation. The liberals and moderate reformers who had supported the manifesto were quickly disillusioned by the Tsar’s refusal to make any real changes. At the same time, the more radical groups, including socialists and Marxists, saw the October Manifesto as little more than a ploy to placate the masses without actually giving them power. As a result, the revolution did not die down; instead, it gave birth to a more organized and radical opposition.

The unrest continued throughout 1905, with workers and peasants staging strikes, uprisings, and even armed rebellions. Revolutionary groups began to form Soviets—workers’ councils—where workers could organize, coordinate, and discuss their grievances. These Soviets played a key role in the 1905 revolution, as they provided a platform for the expression of workers’ demands and helped to coordinate resistance against the Tsarist regime. The formation of these Soviets was a significant moment in the history of the Russian Revolution, as they would later become an essential element of the Bolshevik strategy during the October Revolution of 1917.

In addition to the strikes and uprisings, the military—long a pillar of Tsarist power—began to show signs of disloyalty. Some soldiers mutinied, refusing to carry out orders to suppress the uprisings, while sailors in the Black Sea fleet staged a mutiny, taking control of their ships. This growing unrest within the military was a direct challenge to Nicholas II’s authority and signaled that even the Tsar’s most loyal supporters were beginning to question his leadership.

Despite the widespread nature of the 1905 revolution, it ultimately failed to overthrow the Tsarist regime. The Tsar managed to survive the crisis, largely due to the loyalty of the military and the divisions among the various revolutionary factions. However, the events of 1905 had a lasting impact on Russian politics. They demonstrated the deep dissatisfaction with the Tsarist regime and set the stage for more radical movements, including the rise of the Bolsheviks and the eventual overthrow of the monarchy in 1917. The 1905 revolution may have failed to bring about immediate change, but it showed that the Russian people were no longer willing to passively accept autocracy.

Nicholas II’s Failed Reforms

Tsar Nicholas II’s reign was marked by his failure to fully understand or address the pressing issues facing Russia, which led to increasing discontent and unrest. While his father, Alexander III, had ruled with an iron fist, Nicholas II faced a country that was more politically conscious, more industrialized, and more restless than ever before. Unfortunately, Nicholas lacked the foresight and political skill to navigate these challenges, which led to a series of failed reforms that only deepened the dissatisfaction with his rule.

In response to the 1905 revolution, Nicholas II was forced to make some concessions in order to appease the growing unrest. His October Manifesto, issued on October 30, 1905, promised to establish a Duma—a legislative body that would grant limited political freedoms and represent the interests of the people. It was a significant shift from the Tsarist autocracy, where the Tsar held absolute power, and appeared to signal that Nicholas was willing to share some of his authority. The manifesto also promised civil liberties, including freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom of association, as well as the promise of electoral reform.

However, the October Manifesto was, in reality, a half-hearted attempt to placate the people without actually addressing the root causes of the revolution. The Tsar remained the supreme ruler, retaining the power to dissolve the Duma at will. The reforms were insufficient for the growing demands of the working class and liberals, and Nicholas’s failure to follow through with genuine change only fueled further dissatisfaction. The Duma was essentially a symbolic gesture, with the Tsar retaining the power to veto any legislation that did not align with his personal preferences. This undermined the potential for meaningful reform and caused widespread frustration among those who hoped for a genuine political transformation.

Nicholas also failed to address the deeper issues facing Russia’s industrial workers and peasants. Although he took some steps to modernize Russia’s economy, industrialization in the country was still in its infancy. The working class, particularly in urban centers, lived in appalling conditions. They worked long hours in dangerous factories, endured low wages, and lacked basic labor protections. Nicholas did not enact any significant labor reforms that would improve working conditions or provide workers with more rights. As a result, strikes continued to spread across the country, and labor unrest remained a significant issue throughout his reign.

Meanwhile, the peasantry continued to struggle with poverty and landlessness. Though Alexander II had emancipated the serfs, the land reforms that were supposed to accompany their freedom had not been sufficient. The peasants were burdened with heavy debts and faced exploitative landlords, leaving them in a state of near-permanent poverty. Nicholas did little to address their grievances, and the rural population remained largely dissatisfied with the status quo. The government’s failure to make meaningful land reforms created a fertile ground for revolutionary ideas, including socialism and Marxism, which gained increasing popularity among the working and rural classes.

Another major failure of Nicholas’s reign was his handling of Russia’s military and foreign policy. The Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) was a disaster for Russia, highlighting the weaknesses of the Russian military and exposing the Tsar’s inability to lead the country in times of crisis. The war was fought over territorial disputes in East Asia, and Russia, despite its enormous size, was ill-prepared for such a conflict. The Russian army suffered crushing defeats, and the war’s outcome further embarrassed the Tsarist regime on the world stage. The failure to secure a victory in the Russo-Japanese War not only damaged Russia’s reputation but also intensified domestic unrest, as many people blamed the Tsar for the disastrous military campaign.

Even after the Russo-Japanese War, Nicholas failed to take meaningful steps to address Russia’s military weaknesses or to modernize the army. His approach to reform was piecemeal and ineffective, leading to a continuing sense of frustration among those who saw Russia’s backwardness as a major hindrance to progress. His inability to properly manage the military would have lasting consequences, as the army would later play a central role in the events of the 1917 revolution.

Ultimately, Nicholas II’s reforms were insufficient to address the fundamental issues facing Russia. The October Manifesto, though it promised some concessions, was quickly undermined by the Tsar, and his refusal to make deeper political or economic changes alienated nearly every segment of society. His failure to modernize Russia or address the demands of the people left the country ripe for revolution. Nicholas II’s reign exemplified a lack of political foresight and an unwillingness to engage with the demands of a changing society, leading directly to the collapse of the Tsarist regime in 1917.

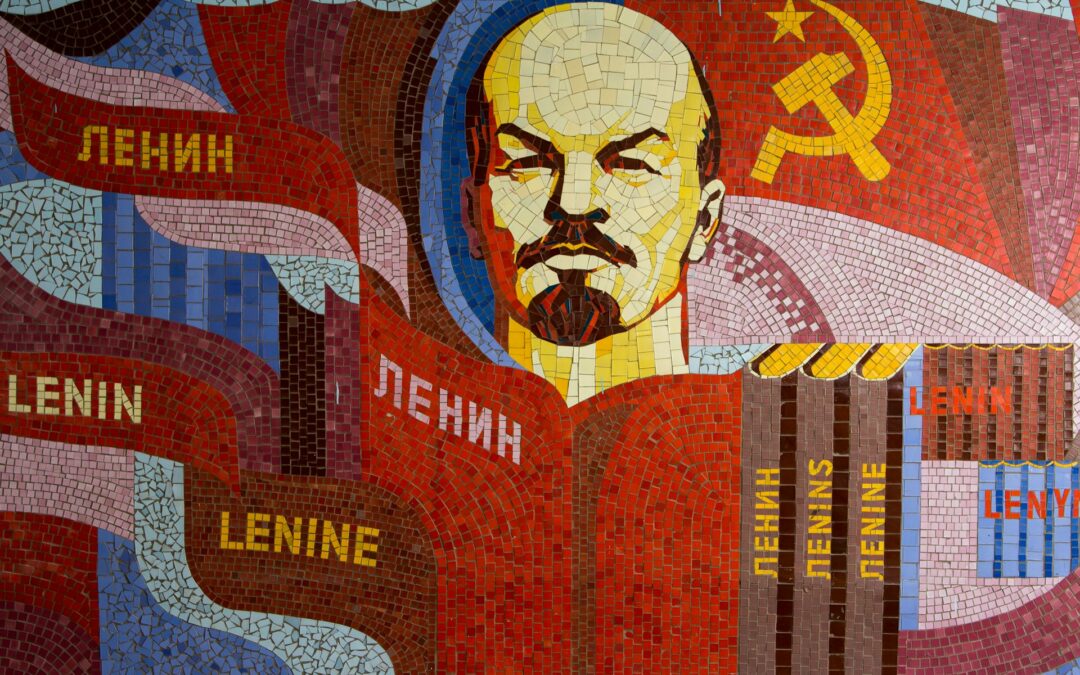

Lenin’s Rise: A Radical Vision

Vladimir Lenin’s path to becoming the central figure in the Russian Revolution was shaped by his personal background, intellectual evolution, and the political climate of the time. Lenin, born Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov in 1870, came from a middle-class family of intellectuals. His early life was marked by tragedy, particularly the execution of his older brother, Alexander, who was involved in a plot to assassinate Tsar Alexander III. This event had a profound impact on Lenin, fueling his desire to bring about revolutionary change in Russia.

Lenin’s political journey was largely shaped by his exposure to Marxism. While studying law at university, Lenin became increasingly involved in radical political activities, eventually embracing the revolutionary ideas of Karl Marx. Marx’s theory of historical materialism, which posited that societies evolve through class struggle and that capitalism would eventually be overthrown by a proletarian revolution, resonated deeply with Lenin. Lenin saw Marxism as the blueprint for understanding the problems facing Russia, and he became a committed advocate for the establishment of a socialist state.

Lenin’s rise within the revolutionary movement was marked by his uncompromising nature and his ability to organize and lead others. He was known for his sharp intellect, as well as his fiery rhetoric and his willingness to challenge both the Tsarist regime and other socialist factions. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Lenin believed that the revolution should be led by a small, disciplined vanguard party of professional revolutionaries, rather than relying on spontaneous uprisings or mass movements. This belief in a centralized, top-down approach to revolution would later distinguish the Bolsheviks, the faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party that he led, from the more moderate Mensheviks.

Lenin’s activism and radicalism eventually led to his exile. In 1895, he was arrested for his involvement in organizing an underground Marxist group and was sentenced to three years of exile in Siberia. During his time in exile, Lenin continued his revolutionary work, writing extensively on Marxism and the political situation in Russia. After his release, he moved to Europe, where he became more deeply involved in the international socialist movement, particularly in organizing Russian Marxists living abroad. While in Europe, Lenin worked to build alliances with other socialist groups and to expand the influence of the Bolsheviks.

One of the defining moments in Lenin’s political career was his response to the 1905 revolution. Lenin was in exile when the revolution broke out, but he closely followed the events unfolding in Russia. The 1905 revolution, though it did not overthrow the Tsar, gave Lenin valuable insights into the weaknesses of the Tsarist regime and the potential for revolutionary change. Lenin saw that the revolution had failed due to a lack of organization and unity among the various factions, and he became determined to create a more effective, centralized revolutionary force. He also recognized that the working class was the key to revolution, and he believed that the Bolsheviks could harness this power to bring about a socialist state.

Lenin’s radical vision for Russia was focused on the creation of a dictatorship of the proletariat, a government led by the working class and based on the principles of Marxism. He believed that only through the overthrow of the Tsarist monarchy and the establishment of a workers’ state could Russia achieve true freedom and equality. However, Lenin’s ideas were not universally accepted among Russian socialists. His uncompromising approach to politics and his insistence on a centralized leadership structure led to a split within the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. The more moderate faction, known as the Mensheviks, rejected Lenin’s methods and beliefs, while the Bolsheviks followed him in advocating for a more radical, authoritarian form of socialism.

As the political situation in Russia continued to deteriorate, Lenin’s influence grew. The failure of the 1905 revolution showed that Russia’s political system could no longer endure without significant change, and Lenin became increasingly convinced that the only way forward was through armed revolution. His writings and speeches, which called for the overthrow of the Tsarist government and the establishment of a dictatorship of the proletariat, inspired a growing movement of workers, intellectuals, and radicals who rallied around his ideas. By the time the 1917 revolution arrived, Lenin was positioned to lead the Bolsheviks in seizing power and overthrowing the Tsarist regime, marking the beginning of a new era in Russian history.

The Role of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin’s rise to prominence within the Bolshevik Party was a critical part of the Russian Revolution’s later stages. While Vladimir Lenin is often credited with the ideological foundation and leadership of the Bolshevik Revolution, Stalin’s role in the party’s organization and his ability to navigate political challenges were central to the Bolsheviks’ success. Stalin was born in Georgia in 1878, and his early life was marked by poverty and hardship. His formative years were spent in the shadow of the Russian Empire’s oppressive rule, and this undoubtedly shaped his views on power and governance.

Stalin’s involvement in revolutionary politics began early. Like Lenin, Stalin was influenced by Marxist theory, but his approach was often more pragmatic and opportunistic. Stalin was initially not a prominent theorist or intellectual within the party, but his rise through the ranks was marked by his ability to build alliances and outmaneuver his rivals. He was a gifted administrator and organizer, qualities that would prove essential as the Bolsheviks worked to seize control of Russia.

One of Stalin’s most important early roles was his work in the party’s clandestine operations. Before the 1917 revolution, Stalin was heavily involved in the Bolshevik’s covert activities, including organizing bank robberies to fund the party’s operations. His involvement in criminal activities to finance the revolution earned him a reputation as a “man of action,” unafraid to use violence and deception to achieve the party’s goals. Although Lenin was initially wary of Stalin’s aggressive tactics, Stalin’s ability to raise funds and organize effectively was invaluable to the Bolshevik cause. He proved to be an essential cog in the machinery that powered the revolution.

Stalin’s influence grew significantly during the period of the Russian Civil War (1917–1922), where he became known for his ruthless leadership. As the civil war raged, Stalin was appointed to several key positions within the Bolshevik government. He played a significant role in overseeing the Red Army and was involved in directing military strategy. His experience during the civil war solidified his reputation as a hard-nosed leader who was willing to do whatever it took to win.

However, it was Stalin’s skill at political maneuvering that truly set him apart within the Bolshevik hierarchy. Stalin was less interested in grand theoretical debates or ideological purity than in consolidating his power. As Lenin’s health began to decline in the mid-1920s, Stalin saw an opportunity to position himself as Lenin’s successor. Lenin, in his final years, began to express concerns about Stalin’s personality and methods, particularly his behavior towards other party members. However, Stalin’s political cunning ensured that he outlasted many of his rivals, including Leon Trotsky, who had been one of the key figures in the revolution and the civil war.

Trotsky, a brilliant military leader and theorist, was seen as the heir apparent to Lenin. However, Stalin skillfully capitalized on Trotsky’s weaknesses, including his abrasive personality and his tendency to alienate potential allies. Stalin’s rise to power was not immediate, but his organizational acumen and ability to appeal to the party’s more pragmatic elements helped him ultimately defeat Trotsky and consolidate his leadership. By the late 1920s, Stalin had become the undisputed leader of the Soviet Union, and his rule would go on to have profound and lasting effects on the country.

Stalin’s leadership was defined by his authoritarianism, his brutal suppression of political dissent, and his efforts to rapidly industrialize the Soviet Union. The terror of Stalin’s purges in the 1930s, in which millions of people were arrested, imprisoned, and executed, has become synonymous with his rule. His rise to power was characterized by the ruthless elimination of political opponents, and his ability to maintain power through fear, violence, and propaganda cemented his place as one of the most powerful and controversial figures of the 20th century.

Though Stalin’s methods were brutal, his role in the revolution and his consolidation of power in the Soviet Union were indispensable. He transformed the Soviet state from a fledgling revolutionary project into a totalitarian regime that would leave a significant imprint on global history.

Rasputin and the Final Years of Tsarism

The last years of Tsar Nicholas II’s reign were marked by scandal, instability, and growing discontent with the monarchy. One of the most bizarre and damaging aspects of this period was the involvement of Grigori Rasputin, a self-styled mystic who came to wield considerable influence over the royal family. Rasputin’s role in the court of Nicholas II and his wife, Alexandra, played a crucial role in the unraveling of the Tsarist regime, as it symbolized the deepening disconnect between the monarchy and the Russian people.

Rasputin was a peasant from Siberia, and his rise to prominence was as improbable as it was scandalous. He claimed to possess healing powers and became known for his ability to ease the suffering of the Tsar’s only son, Alexei, who suffered from hemophilia, a rare and life-threatening blood disorder. Alexandra, deeply devoted to her son and desperate for a solution, became increasingly reliant on Rasputin’s “healing” abilities, and soon he became an influential figure in the royal court.

Although Rasputin’s influence over the royal family began as a purely personal matter, it soon extended into political affairs. Alexandra, who was heavily involved in managing the day-to-day affairs of the empire due to Nicholas II’s frequent absences, trusted Rasputin deeply and even sought his advice on political matters. The Tsar’s absence from the capital during World War I, coupled with his reliance on Rasputin, led to widespread rumors and suspicions that Rasputin was controlling the monarchy from behind the scenes.

Rasputin’s influence over Alexandra and the royal family angered many members of the Russian aristocracy, who saw him as a dangerous and unqualified figure. His relationship with the royal family was a source of constant scandal, and the press, both inside and outside Russia, eagerly reported on his eccentricities, his womanizing, and his apparent disdain for the conventions of Russian society. Rasputin was known for his heavy drinking, his bizarre behavior, and his often mystic claims. This created an aura of scandal around the royal court, further alienating the Russian people, many of whom were already disillusioned with Tsar Nicholas II’s failure to address their grievances.

Rasputin’s growing influence was particularly problematic because he was seen as unqualified and morally corrupt, yet his advice was sought by the Tsar and his wife on issues of governance. His ability to maintain such a prominent position in the royal court despite his controversial behavior exacerbated the perception that the Tsarist regime was disconnected from the real concerns of the Russian people. Many believed that Rasputin was exploiting the royal family for his own gain, and his influence was seen as a symbol of the monarchy’s moral decay.

The final years of Tsar Nicholas II’s reign were plagued by Rasputin’s scandals, which served to further undermine the legitimacy of the monarchy. The Tsar’s inability to distance himself from Rasputin, despite the widespread rumors and public outcry, further tarnished his image as a ruler. Eventually, Rasputin’s influence would lead to his own violent death. In December 1916, a group of nobles, frustrated with Rasputin’s power over the royal family, conspired to assassinate him. The story of Rasputin’s death—he was poisoned, shot, and eventually drowned—has become legendary, adding another layer of intrigue and mystery to his already bizarre legacy.

While Rasputin’s death marked the end of his direct influence over the royal family, the damage had already been done. His connection to the monarchy served as a focal point for public discontent, and the scandal surrounding his relationship with the Tsar and Tsarina only deepened the rift between the royal family and the Russian people. As World War I continued to devastate Russia, the Tsar’s image was irreparably damaged by the public’s perception of his incompetence, his wife’s reliance on Rasputin, and his failure to address the deep economic and political issues facing the country.

Rasputin’s influence on the royal family, though short-lived, had long-lasting repercussions for the Russian monarchy. His involvement symbolized the monarchy’s growing disconnection from the people, and his scandals highlighted the weaknesses and dysfunction of the imperial system. By the time of the February Revolution in 1917, the Russian people had lost faith in their Tsar, and the monarchy itself was on the brink of collapse. Rasputin, in many ways, became the embodiment of the royal family’s inability to govern effectively, and his legacy would remain a lasting symbol of the downfall of the Tsarist regime.

Conclusion

The fall of the Tsarist regime in 1917 was not the result of a single event but the culmination of years of political failure, societal unrest, and revolutionary fervor. Nicholas II’s inability to recognize the changing tide and make meaningful reforms left the Russian people with no other option but to rise up. The influence of figures like Rasputin only further discredited the monarchy, while Lenin and his Bolshevik followers laid the foundation for a new order. Though the 1905 revolution and Nicholas’s failed reforms showed glimpses of potential change, the Tsars’ refusal to fully embrace modernization ultimately led to their downfall. The Russian Revolution stands as a testament to the importance of political responsiveness and reform in the face of growing social discontent. It forever changed the course of Russian history and heralded the dawn of the Soviet era.