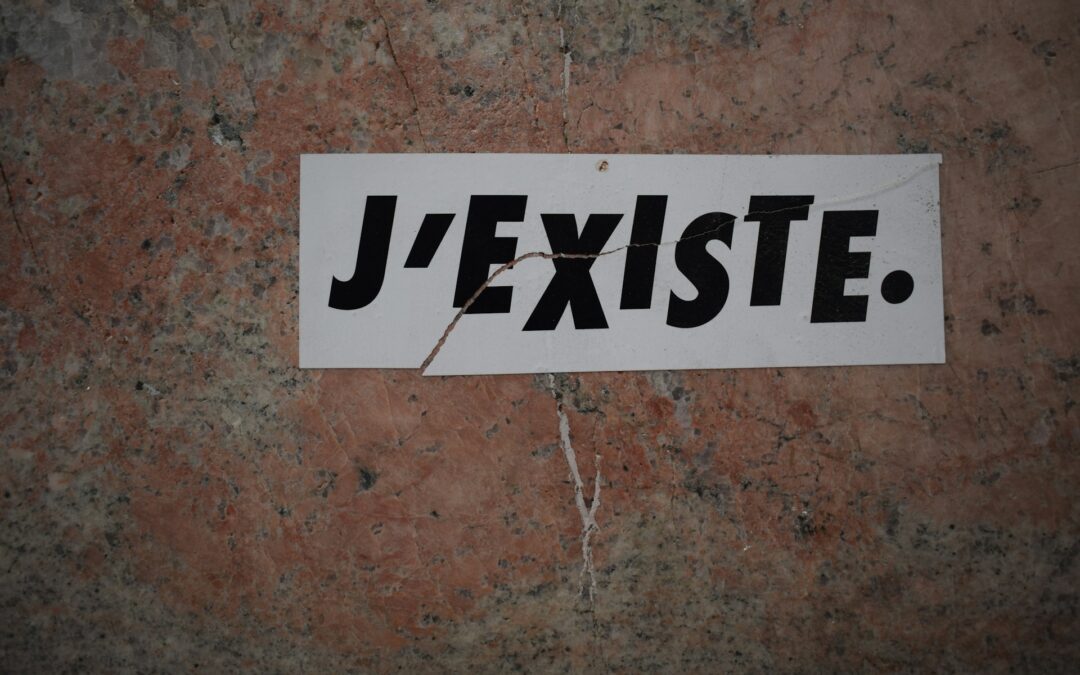

Existentialist philosophy often stirs discomfort, challenging the foundation of how we perceive ourselves and the world around us. One of its most unsettling concepts is the idea of freedom—and how our relationship to it can shape our lives and the very essence of who we are. Simone de Beauvoir, a towering figure in existentialist thought, explored this tension between freedom and how it is often rejected. Her ideas, particularly around the concept of the “subhuman,” provide a piercing lens through which we can examine our lives and the dangers of evading freedom. This is the existential crisis we can’t afford to ignore.

Freedom: A Gift and a Burden

Freedom, at its most fundamental level, is the most powerful gift humanity has. It is the very thing that distinguishes us from the rest of the natural world, as it endows us with the capacity to make decisions, to choose our actions, and to forge meaning in a world that does not offer it on its own. But this freedom is not a simple gift. It comes with immense responsibility and inherent challenges.

Simone de Beauvoir, in her exploration of existentialism, presents freedom as an ambiguous concept—one that is both exhilarating and daunting. The realization that we are free to shape our own destinies can be liberating, yet it also casts a shadow of responsibility. Unlike other creatures, whose lives are shaped by instincts or external forces, we are asked to create purpose in a world that offers none. It is up to each individual to define what their life will mean, to decide what principles will guide their actions, and to engage with the world in a meaningful way.

However, the weight of this freedom can be overwhelming. There is no roadmap for how to navigate life’s complexities, and the absence of external guidance often leads to confusion, uncertainty, and fear. This anxiety is at the core of existential philosophy. The question “What should I do with my life?” is not just a passing concern, but a profound challenge that can paralyze those who feel unprepared to confront it. Freedom means we must choose—yet with each choice comes the awareness that we could have chosen differently, that the path we take is, in a sense, irreversible.

This ambiguity of freedom is what makes it both a gift and a burden. On the one hand, we are free to create meaning, to challenge norms, and to define our own values. On the other, we are constantly confronted by the uncertainty of what those choices will lead to. What happens if we choose wrong? What if we disappoint ourselves or others? The inability to predict the outcome of our choices means we live in a constant state of vulnerability. There is no way to fully prepare for the consequences of our actions—there is only the necessity to act, to keep moving forward in the face of uncertainty.

Ultimately, freedom is both liberating and daunting because it requires the individual to take full responsibility for their life. This is what existentialism asks of us: to embrace freedom, to understand its complexity, and to carry the weight of our choices with courage and authenticity.

The Subhuman and the Serious Person: Denying Freedom

In The Ethics of Ambiguity, Beauvoir presents two key figures who exemplify ways in which people deny their freedom and the responsibility that comes with it: the serious person and the subhuman. Both of these figures represent attempts to avoid engaging with freedom in its full, unfiltered form.

The serious person is someone who chooses to surrender their freedom to external systems, ideologies, or roles. These individuals seek meaning in predefined structures—whether that be religion, politics, or societal expectations. By immersing themselves in an external purpose, the serious person avoids the discomfort of facing their own freedom. Rather than embracing the ambiguity of existence and defining their own path, they prefer to follow a ready-made set of values or ideologies.

This need for external validation and structure arises from a deep-seated fear of freedom itself. The serious person does not wish to confront the daunting responsibility of shaping their life authentically. Instead, they seek refuge in systems that promise certainty and stability. Whether it is through dedicating themselves to a political cause, adhering strictly to religious doctrine, or defining themselves by their professional roles, the serious person’s life is one of conformity to external expectations.

However, in doing so, the serious person fails to engage fully with their own subjectivity. They give up the authentic freedom to shape their life in favor of a comfortable predictability. This surrender to external values allows them to avoid making difficult decisions about who they are and what their life should be. While the serious person may appear engaged in the world, they are ultimately just playing a role dictated by the systems they subscribe to. They do not actively choose to engage with their freedom—they are, in essence, slaves to the ideologies they adopt.

On the other hand, the subhuman takes a much darker approach to the denial of freedom. Unlike the serious person, who at least actively commits to an external cause, the subhuman drifts passively through life, avoiding any semblance of responsibility. They reject the idea that they can shape their own lives and instead submit entirely to the circumstances they find themselves in. The subhuman defines their existence through a passive acceptance of their “facticity”—the external facts of their situation, such as their social class, genetic makeup, or upbringing.

The subhuman does not seek to transcend their circumstances; rather, they accept them as fixed and unchangeable. Life is something that happens to them, rather than something they actively participate in. They cope with this reality by indulging in distractions—video games, mindless social media scrolling, and entertainment that numbs them to the existential questions that might otherwise plague them. They do not engage with the meaning-making process because they believe it is futile. Their mantra becomes, “It’s over,” and they resign themselves to a life of passivity.

Unlike the serious person, who at least attempts to seek purpose, the subhuman has surrendered entirely. They do not take ownership of their actions, nor do they attempt to define their place in the world. The subhuman is a passive observer of life, constantly fleeing from the discomfort that comes with confronting freedom. Yet, in their passivity, they become dangerously vulnerable to manipulation. Their lack of agency makes them susceptible to being co-opted by external forces, whether that be ideologies, political movements, or even oppressive systems. Because the subhuman does not engage with the world critically, they become easy targets for those seeking to exploit them.

In both cases, whether through the serious person’s devotion to external values or the subhuman’s abdication of responsibility, the individual avoids the fundamental challenge of freedom: making authentic choices and shaping one’s life. Both figures fail to engage with their own power, and in doing so, they lose the opportunity to live genuinely.

The Danger of the Subhuman

The subhuman represents the ultimate failure to engage with one’s freedom. While the serious person seeks meaning in external structures, the subhuman rejects even the possibility of meaning-making. Beauvoir warns that the subhuman is not just an apathetic individual—they are a dangerous figure, both to themselves and to society.

The subhuman’s refusal to engage with their own freedom makes them profoundly vulnerable. Because they see themselves as victims of their circumstances, they are open to adopting ideologies or beliefs without ever questioning them. They passively accept whatever comes their way, whether it be a political ideology, a social group, or a set of values. They have no anchor of their own; their identity is shaped by whatever external force is most immediately available to them.

This passivity makes the subhuman highly susceptible to manipulation. In times of political upheaval or societal unrest, it is often the subhuman who becomes the foot soldier for tyrants and authoritarian regimes. They are the ones who follow blindly, who commit acts of violence or oppression without understanding why or questioning the morality of their actions. The subhuman is an instrument of others’ wills, a mindless participant in systems that dehumanize and oppress.

Beauvoir’s warning is clear: to reject one’s freedom is not a harmless decision. The subhuman’s disengagement from their own responsibility makes them complicit in the larger forces of injustice. They are not innocent bystanders; they are part of the problem. The subhuman’s passivity allows them to become pawns in larger ideological games. They may lack the power to shape the world, but their lack of engagement with their own agency allows others to exploit them for their own purposes.

Moreover, the subhuman’s passivity has a corrosive effect on society as a whole. When large groups of people retreat into passivity and abdicate their responsibility, society becomes fragmented and disempowered. The subhuman is, in a sense, the ultimate embodiment of what happens when individuals abandon their freedom. They allow themselves to be shaped entirely by external forces, and in doing so, they perpetuate systems that thrive on control, manipulation, and oppression.

The subhuman is not just a figure of existential concern; they are a social and political danger. They are a reminder that freedom is not just a personal challenge—it is a collective responsibility. To engage with freedom means to shape the world around us, to take responsibility for our actions, and to resist the forces that would seek to control us. In rejecting this responsibility, the subhuman contributes to the very systems that diminish the possibilities of freedom for everyone.

The Serious Person: A Step Toward Subhumanity?

The serious person is, in many ways, the precursor to the subhuman. While not as entirely passive as the subhuman, the serious person’s refusal to embrace freedom in its fullest sense makes them a potential stepping stone toward existential disengagement. The serious person’s life revolves around external values, ideals, or ideologies—things that they adopt wholesale without question. These external systems provide a sense of stability and purpose, but in doing so, they strip away the individual’s authentic engagement with their freedom.

At first glance, the serious person might seem more engaged in life than the subhuman. They are active participants in a cause, committed to an ideology, or devoted to a particular role, such as that of a parent, a professional, or a member of a social group. They cling to these roles as if they provide the meaning that the individual cannot generate for themselves. In fact, the serious person may appear highly responsible—someone who devotes their life to a cause or mission greater than themselves. However, this devotion is not an act of freedom but an act of surrender.

In Beauvoir’s terms, the serious person is someone who has chosen to “get rid of” their freedom by submitting it to an external source. Whether it is a political party, a religious doctrine, or a corporate culture, the serious person’s existence is defined by the values and beliefs of the group or system they adhere to. They do not question these values but rather accept them as absolutes, as a way of avoiding the ambiguity and uncertainty of freedom. The serious person is not willing to step into the discomfort of defining their own life and purpose; instead, they prefer the security of a prescribed identity.

The problem with this approach is that it keeps the serious person tethered to external definitions of meaning. They do not engage with their true self; instead, they engage with a self that is constructed by the ideology or role they occupy. This means that their identity is contingent, unstable, and vulnerable to collapse. What happens if the values they have built their life around are suddenly called into question or exposed as flawed? What happens when the external structures that provide them with meaning begin to erode?

In these moments of crisis, the serious person risks falling into the subhuman state. Without the solid foundation of external values to lean on, they may become lost, uncertain, and unable to make meaning from their lives. The collapse of external ideologies or roles often leads the serious person to confront the same existential void that the subhuman avoids altogether. In essence, the serious person’s life is a fragile house of cards that, if disrupted, could unravel completely, leaving them adrift in the same passive, directionless state that characterizes the subhuman.

This transition from serious person to subhuman illustrates the inherent instability of surrendering one’s freedom to external values. Both figures fail to engage fully with their own subjective experience and lack the ability to define their lives in a way that is authentic and personally meaningful. The serious person’s identity, like the subhuman’s, is shaped by outside forces—whether ideologies, roles, or societal expectations. The shift from the serious person’s over-reliance on external systems to the subhuman’s utter rejection of freedom is a slippery slope. If the serious person is not careful, they risk losing themselves entirely.

The Freedom to Choose

Freedom, in its most powerful form, is the ability to choose—actively and authentically. It is not a passive state, nor is it something that happens to us. Freedom, in the existentialist sense, means engaging with the world in a way that is intentional, responsible, and reflective. We are free, not because we are devoid of constraints, but because we have the capacity to make decisions in the face of those constraints.

However, freedom is not simply about making choices; it is about how we make them. Many people avoid making choices at all, preferring to surrender to external values or circumstances. The serious person seeks comfort in external systems that promise security and meaning. The subhuman avoids responsibility altogether, choosing to let life happen to them rather than taking an active role in shaping their own destiny. But true freedom lies in the ability to choose in a way that is deeply personal and authentic—where each decision reflects who we are and the values we choose to live by.

Beauvoir’s notion of “facticity” is crucial here: it refers to the facts of our existence—the conditions and circumstances that define our lives. These facts can be anything from our social class to our physical health, from the time period in which we live to the relationships we have. Facticity represents the external forces that shape us, but it does not define us. What defines us is how we respond to these forces. The painter who faces financial struggles and societal apathy toward her work is still free to create; she may be constrained by external forces, but her freedom lies in how she chooses to engage with those constraints.

To choose freely is to transcend these external factors, to actively engage with life in a way that reflects our deepest desires, values, and aspirations. This does not mean that we are free from limitations—rather, it means that we are free to act despite those limitations. The existentialist approach to freedom is not about rejecting all constraints but about taking responsibility for how we navigate them. We cannot choose the circumstances of our birth or the challenges we face, but we can choose how we respond to them.

This ability to choose is what gives life meaning. It is not the circumstances that make us who we are, but our responses to those circumstances. In a sense, freedom is a dynamic process. It is not a fixed state but an ongoing engagement with the world in which we actively make meaning. In choosing how to act in the face of adversity, we define ourselves—not by the limitations of our facticity, but by the way we transcend them.

The freedom to choose is not without its challenges. It requires self-awareness, responsibility, and a willingness to confront uncertainty. Making authentic choices means rejecting easy answers, stepping into discomfort, and taking ownership of the consequences of our decisions. But it is only through this active engagement with freedom that we can shape our lives in a way that is truly meaningful.

The Existentialist Solution: Embrace Freedom

The existentialist solution to the crisis of freedom is simple, yet profoundly difficult: embrace it. To embrace freedom is to engage with life fully and responsibly, to step into the ambiguity and uncertainty of existence and make meaningful choices despite it. It means rejecting passivity and external systems that promise certainty, and instead creating meaning through our own actions and decisions.

Beauvoir’s concept of the “ethics of ambiguity” calls us to navigate life with a recognition of its inherent uncertainty. There are no fixed answers, no absolute truths, and no ready-made purposes. Life is not something that happens to us—it is something we actively create. The existentialist does not wait for meaning to come from outside; they create it from within. This means acknowledging that freedom is not just an abstract idea but a practical force in shaping our lives.

Embracing freedom also means taking responsibility for our choices. It is not enough to simply acknowledge our freedom—we must actively use it to shape the world around us. The decisions we make affect not only our own lives but the lives of others. This is where the concept of responsibility becomes central. When we choose freely, we do not choose in isolation. Our choices reverberate throughout society, and we must recognize the impact they have on others.

Beauvoir also emphasizes that freedom is not something that can be fully realized alone. As human beings, we are interconnected, and our freedom is bound up with the freedom of others. True freedom involves recognizing the interdependence of all people and taking responsibility for our role in shaping the world. It is not enough to simply be free ourselves; we must also help others achieve their freedom. This relational aspect of freedom calls for empathy, solidarity, and a commitment to the collective well-being.

In embracing freedom, we must also accept its inherent challenges. Freedom means that we are constantly confronted with choices—some small, some monumental. Each decision requires us to reflect on our values, to confront the ambiguity of existence, and to take responsibility for the consequences of our actions. But this is the price of authenticity. By engaging fully with our freedom, we not only create meaning in our own lives but also contribute to a more meaningful and just world.

To live authentically, then, is to embrace the complexity of freedom—to step into the unknown, to reject the comfort of external systems, and to shape our lives in a way that reflects our deepest values. This is the existentialist path, and though it is fraught with difficulty, it is the only way to live a life that is truly our own.

Conclusion

In the face of existential freedom, we are confronted with a powerful and often uncomfortable choice: to engage with life authentically or to retreat into passivity. Simone de Beauvoir’s exploration of the subhuman and the serious person reveals the dangers of evading responsibility and avoiding the anxiety that comes with freedom. While the serious person seeks solace in external systems of meaning, the subhuman completely disengages, leaving both types vulnerable to manipulation and tyranny. The existentialist path, however, challenges us to embrace the ambiguity of freedom—to take responsibility for our choices and shape our lives despite our constraints. Only through actively engaging with our freedom, accepting its weight, and creating meaning can we live authentically. This existential journey is not easy, but it is the only one that leads to true self-determination and a life lived on our terms. The choice is ours: to remain passive and be shaped by others or to step into the discomfort of freedom and forge our path.