The American Revolution, a defining moment in history, was a complex saga of rebellion, resilience, and revolution. The process that eventually led to the birth of the United States was anything but straightforward, and as with many monumental moments in history, the story was shaped by a mix of misguided decisions, untimely reactions, and dramatic acts of defiance. This article will take you on a journey from the discovery of the New World to the first shots of the Revolution, exploring the events that built the momentum for America’s fight for independence.

Christopher Columbus and the Discovery of the New World

Christopher Columbus, an Italian-born navigator, set out on his fateful voyage across the Atlantic in 1492 under the auspices of the Spanish monarchy. His objective was straightforward: to find a faster route to the lucrative markets of India and China by sailing westward. Columbus believed, along with many others at the time, that the world was smaller than it actually was and that one could simply sail west to reach the East. What he did not anticipate was that the vast ocean he would encounter was the Atlantic, which separated Europe from the undiscovered continents of the Western Hemisphere.

When Columbus landed in the Caribbean in October 1492, he thought he had reached Asia, specifically the islands off the coast of India. He was unaware that he had encountered an entirely new world, though he quickly claimed the land for Spain. This initial misunderstanding didn’t detract from the significance of his journey. Columbus’ discovery marked the beginning of an era of European exploration and colonization in the Americas, fundamentally altering the course of history.

However, Columbus’ interactions with the indigenous populations were anything but peaceful. Upon landing, Columbus and his crew embarked on a violent campaign of conquest. They enslaved and exploited the native peoples, subjecting them to forced labor and violent treatment in the pursuit of gold and other resources. Columbus’ legacy in the Americas is therefore deeply controversial, as his exploration led to the widespread death and displacement of indigenous peoples across the continent.

Upon returning to Spain, Columbus was heralded as a hero. He was feted by the Spanish monarchy, and his discoveries were seen as a gateway to untold riches and territories. Columbus brought back treasures including gold, exotic goods like tobacco and pineapples, and strange animals such as turkeys. The fame and riches generated by his discoveries fueled further European exploration and colonization. Despite Columbus’ monumental “discovery,” however, he was not the first European to reach North America. The Norse, led by Leif Erikson, had established settlements in what is now Newfoundland around the year 1000. Their exploration of North America, however, did not result in lasting settlements, and their legacy was soon overshadowed by the European wave of expansion triggered by Columbus’ voyages.

Columbus’ arrival in the Americas set off a scramble for territorial claims between European powers. Spain, Portugal, France, and England all raced to explore and colonize the newly discovered lands. This marked the beginning of a period of intense rivalry and warfare in the New World, the effects of which would ripple through history for centuries to come. Columbus’ discovery may have been accidental, but it set in motion a period of European dominance in the Americas that would last for centuries.

The French and Indian War: The Seeds of Rebellion

By the mid-18th century, the European powers in North America were entangled in a fierce struggle for dominance. While Britain controlled the eastern seaboard and the Caribbean, France had established a vast empire in Canada and along the Mississippi River. Both nations, along with their respective Native American allies, sought to control the fertile lands and valuable trade routes of the interior, especially the Ohio River Valley. This area, rich in resources, became the flashpoint for what would soon erupt into the French and Indian War (1754-1763).

The conflict began with a series of territorial disputes. In 1754, the French began constructing forts along the Ohio River to solidify their control over the area. The British, who also claimed the region, saw this as a direct threat to their interests. A young Lieutenant Colonel George Washington was sent by the British to confront the French and assert British authority. The confrontation led to a skirmish in which Washington’s forces killed the French commander, an act that ignited a full-scale war.

The French and Indian War was part of the larger Seven Years’ War, which spanned the globe and pitted Britain and its allies against France and its partners. On the North American front, the war was characterized by alliances between European powers and various Native American tribes. The French generally allied with the Algonquin and Huron tribes, while the British sided with the Iroquois Confederacy. The war was not just a battle for territory, but for control over the fur trade, a lucrative industry that spanned the continent.

After nearly a decade of fighting, Britain emerged victorious. The Treaty of Paris (1763) marked the end of the war, with Britain gaining control of all French territories east of the Mississippi River, including Canada. Spain, an ally of France, ceded Florida to Britain in exchange for the return of Havana, Cuba. Though Britain had won the war, the cost was immense. The war had drained the British treasury, leaving the nation deeply in debt. This financial burden would later become a major source of friction between Britain and its American colonies, setting the stage for rebellion.

The victory over France left Britain in a dominant position in North America, but the costs of war were not just financial. The British government now had to manage a much larger empire, which required an increased military presence and control over the colonies. The colonists, who had grown accustomed to a degree of self-governance, were now faced with an intrusive British presence. This tension would soon explode as Britain attempted to extract revenue from the colonies to pay for the war’s expenses, leading to the passage of unpopular taxes that would spark the American Revolution.

Britain’s Attempts to Refinance through Taxation

After the French and Indian War, Britain found itself in a precarious financial position. The £60 million debt incurred during the conflict was staggering, and the British government was desperate to find a way to repay it. Instead of imposing new taxes on British citizens, who were already burdened with taxes from previous conflicts, Britain turned its attention to the American colonies. The British government felt that the colonies, which had benefitted from British protection during the war, should contribute to the costs of their own defense.

The first major tax imposed on the colonies was the Sugar Act of 1764, which was designed to raise revenue by taxing molasses and sugar imported into the colonies. This law specifically targeted merchants and traders who relied on imported goods, but it was largely ignored in the colonies. Many colonists continued to smuggle molasses from the French Caribbean to avoid the tax, which Britain was unable to effectively enforce.

In 1765, Britain introduced the Stamp Act, which imposed a direct tax on all printed materials in the colonies, including newspapers, legal documents, and playing cards. This tax was deeply unpopular, as it was a direct form of taxation that affected a wide cross-section of colonial society. The Stamp Act was the first instance in which the British government taxed the colonies without their consent, and it enraged the colonists. They argued that it violated their fundamental rights as Englishmen to be taxed only with their consent, and they coined the famous phrase, “No taxation without representation.”

The colonists responded with fierce protests. In cities across the colonies, crowds rioted, shopkeepers refused to sell stamped paper, and lawyers, printers, and merchants led a boycott of British goods. The protests were not only widespread but also organized, with groups like the Sons of Liberty forming to coordinate resistance. In response, British businesses, which were losing money due to the colonial boycott, pressured Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act. After a year of protests and economic pressure, Britain relented and repealed the law in 1766. However, the victory was short-lived.

Despite the repeal, Britain continued to impose taxes on the colonies. In 1767, the Townshend Acts were introduced, which placed duties on imports such as glass, tea, lead, and paper. This new series of taxes once again angered the colonists, who believed that Britain was trying to assert control over them without their consent. Once again, the colonists responded with boycotts and protests. The British, unable to quell the unrest, eventually repealed most of the Townshend duties in 1770, leaving only the tax on tea in place. However, the damage had been done. The colonists had made it clear that they would not tolerate any form of taxation without representation, and the British government’s attempts to raise revenue only served to deepen the rift between the colonies and Britain.

By this point, it was clear that the relationship between the colonies and Britain was irreparably damaged. What had started as a financial dispute had grown into a fundamental question of governance and rights. As British control tightened and the colonies resisted, the stage was set for open rebellion, a rebellion that would soon erupt into the American Revolution.

The Boston Massacre and Rising Tensions

The growing discontent in the American colonies was not just about taxes; it was also about the increasing presence of British soldiers in the colonies. After the passage of the Townshend Acts, which imposed duties on various imports, tensions between the British government and the American colonists escalated. In 1768, to enforce these new laws and maintain order, the British government sent troops to Boston, one of the most rebellious cities. The sight of redcoats patrolling the streets, especially in Boston, where the population was staunchly anti-British, only deepened the animosity.

The British soldiers in Boston were seen as an occupying force, an oppressive symbol of Britain’s control over the colonies. Relations between the troops and the locals were tense, and small altercations were frequent. This was a volatile situation just waiting for an explosive moment.

On March 5, 1770, that moment arrived. A crowd of colonists gathered around a British sentry at the Customs House, hurling insults and throwing snowballs at the soldier. The tension quickly escalated, and soon, more British soldiers arrived to support their comrade. The crowd grew larger, and the insults became more hostile. The soldiers, feeling threatened, were caught in a situation where their nerves began to fray. Suddenly, one of the soldiers fired into the crowd, followed by several others. Five colonists were killed, including Crispus Attucks, an African-American man who would later be regarded as the first martyr of the American Revolution.

The Boston Massacre, as it came to be known, was a pivotal event. While the British claimed they acted in self-defense, many in the colonies saw it as a deliberate attack on innocent civilians. Patriot leaders like Samuel Adams used the event to stoke anti-British sentiment, portraying the massacre as proof of the British government’s cruelty. The colonists’ anger only intensified, and the Massacre became a rallying point for those who wanted independence from British rule.

In response to the tragedy, the British government acted quickly to defuse the situation. They allowed some of the soldiers involved in the shooting to stand trial, where they were defended by none other than John Adams, a future leader in the Revolution. Two soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter, while the rest were acquitted. Despite this legal outcome, the emotional damage had already been done. The Massacre fueled the flames of rebellion, and the event became an iconic symbol of British oppression in the colonies. The growing animosity was evident, and it was clear that the tensions between Britain and its colonies were now a matter of life and death.

The Coercive Acts and Colonial Unity

In the aftermath of the Boston Tea Party in December 1773, the British government decided to take drastic measures to punish Massachusetts and to set an example for the other colonies. The Boston Tea Party, an act of rebellion in which colonists, disguised as Native Americans, dumped 342 chests of tea into Boston Harbor in protest of the Tea Act, had embarrassed the British government and symbolized the colonies’ defiance. As a result, Britain passed the Coercive Acts, known in the colonies as the Intolerable Acts, in 1774. These laws were designed to punish Massachusetts, suppress the rebellious spirit of the colonists, and assert British authority.

The first of the Coercive Acts was the Boston Port Act, which closed the Port of Boston until the East India Company was reimbursed for the destroyed tea. This act effectively crippled Boston’s economy, as the port was one of the busiest and most vital in the colonies. The second act, the Massachusetts Government Act, took away much of Massachusetts’ local autonomy. The royal governor now had more control over local affairs, including the right to dissolve the colonial assembly at will. The third act, the Administration of Justice Act, allowed British officials accused of crimes to be tried in Britain or another colony, further eroding the power of local colonial courts. Finally, the Quartering Act, which required colonists to house and supply British troops, was extended to allow British troops to be housed in private homes in Massachusetts.

The British government’s decision to implement these harsh measures not only punished Massachusetts but also inadvertently united the colonies against Britain. Colonists in other parts of America were alarmed at the erosion of their rights and liberties, and they saw the actions of the British government as an attack on the entire colonial system. The Intolerable Acts sparked outrage, and colonists from various regions began to form a sense of unity and common purpose.

In response, the colonies convened the First Continental Congress in September 1774, meeting in Philadelphia. Fifty-six delegates from twelve colonies gathered to discuss a unified response to British aggression. Prominent figures like George Washington, Samuel Adams, and John Adams were present. The Congress decided to take several actions, including issuing a Declaration of Rights and Grievances, which outlined the colonies’ objections to British policies, and establishing a boycott of British goods. They also called for a second Continental Congress to convene the following year if their demands were not met.

Although the First Continental Congress did not call for independence, it marked the first collective action of the colonies in resistance to British authority. The unity displayed in Philadelphia was a significant step toward the American Revolution, as it demonstrated that the colonies could work together in defiance of Britain. The Coercive Acts, meant to break the spirit of the colonies, instead had the opposite effect: they galvanized the American colonists and sparked the beginning of a unified struggle for freedom and independence.

The Shot Heard ‘Round the World: The Start of the Revolution

By the spring of 1775, the political and economic tensions between the American colonies and Great Britain had reached a breaking point. The British government, eager to suppress the growing rebellion, sought to disarm the colonists by seizing their weapons. In April 1775, General Thomas Gage, the British commander in Boston, received orders to march into the countryside and capture the colonial militias’ stockpiles of arms and ammunition. The British troops set their sights on Concord, a town in Massachusetts where the colonists had stored weapons.

However, the colonists were well aware of the British plans. Patriot leaders like Paul Revere and William Dawes had set up a system of riders to alert the militias of any British movements. On the night of April 18, 1775, Revere and Dawes famously rode out to warn the countryside that the British were coming. The message spread quickly, and the militias began to mobilize. By the time the British troops arrived in Lexington on the morning of April 19, the colonists were ready for them.

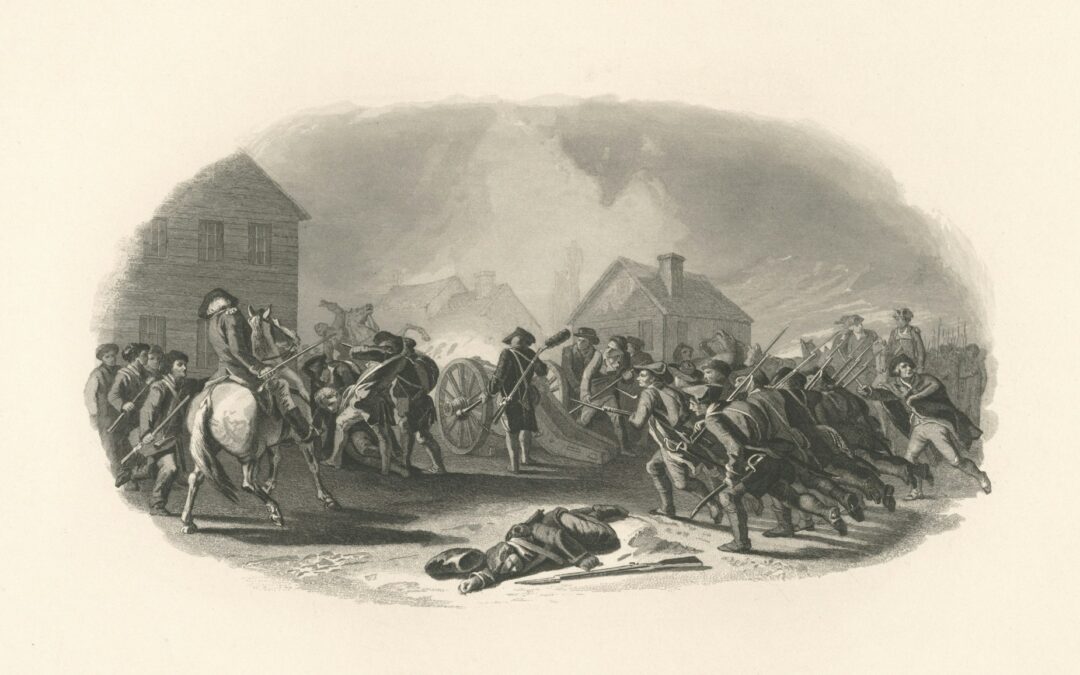

In Lexington, a small group of colonial militiamen, known as the Minutemen, confronted the British soldiers. It is still unclear who fired the first shot, but within moments, gunfire rang out. The “shot heard ‘round the world” was fired, marking the beginning of the American Revolution. The skirmish left eight colonists dead, and the British soldiers continued on to Concord, where they faced a much larger force of rebels.

At Concord’s North Bridge, the militia engaged the British in a more organized and determined fight. The colonists pushed the British back, forcing them to retreat to Boston. The British, who had expected an easy victory, were shocked by the resistance they encountered. As the British retreated, more and more colonial militias joined the fight, and along the route back to Boston, the British troops were harassed by gunfire from behind trees and walls.

By the time the British reached Boston, they had suffered heavy casualties. The colonists, though outnumbered and less well-equipped, had demonstrated that they could stand up to the British military. The Battle of Lexington and Concord was a turning point. It was no longer just a protest; it was open rebellion. The colonists had fired the first shots of the American Revolution, and the fight for independence had begun in earnest.

This early victory for the colonists was a massive morale booster and a rallying cry for those still undecided about the cause of rebellion. The British, meanwhile, realized that the conflict would not be easily won. The war had officially begun, and it would continue for the next eight years, with the American colonies fighting for their right to self-determination and independence.

Benedict Arnold and Fort Ticonderoga

As the Revolutionary War began in 1775, one of the most significant early victories for the Continental Army came at Fort Ticonderoga, located in upstate New York on the shores of Lake Champlain. The fort had been a key British stronghold during the French and Indian War, but by the time of the American Revolution, it held valuable artillery, including cannons and other weapons that would be crucial to the colonists’ efforts. The fort was lightly defended by British forces, which made it a prime target for the rebels.

Benedict Arnold, a militia officer from Connecticut, saw the strategic importance of Fort Ticonderoga and conceived a plan to capture it. However, he was not alone in his ambition. Ethan Allen, the leader of the Green Mountain Boys, a group of local militia fighters from Vermont, also sought to seize the fort. The two men, both eager for glory and recognition, independently arrived at the idea of attacking Ticonderoga. Realizing they had similar goals, Arnold and Allen reluctantly decided to join forces.

Despite their combined efforts, there was significant tension between the two men over who should lead the operation. Both Arnold and Allen were determined to take charge, which led to a series of arguments over leadership and strategy. However, when it became clear that the Green Mountain Boys would go home if they were not given control of the operation, Arnold eventually conceded to Allen, who led the group to the fort.

The attack on Fort Ticonderoga took place in the early hours of May 10, 1775. The British garrison, caught off guard and unaware of the attackers’ presence, offered little resistance. The fort was quickly taken with minimal casualties. The rebels not only secured the fort but also seized its cache of valuable artillery, which would play a pivotal role in later battles.

Despite his involvement in the successful capture of the fort, Benedict Arnold’s role was overshadowed by Ethan Allen’s leadership. In the aftermath, Arnold felt slighted and disregarded. This sense of injustice would only grow as Arnold became more frustrated with the Continental Congress and his lack of recognition. Over the course of the war, Arnold’s sense of betrayal grew, ultimately leading him to defect to the British side in 1780. His decision to commit treason by planning to surrender the strategic fort at West Point to the British marked one of the most notorious acts of betrayal in American history. The capture of Fort Ticonderoga, while a success, was the first sign of Arnold’s growing discontent with the revolutionary cause.

Washington Takes Command: The Siege of Boston

In June 1775, George Washington was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army by the Second Continental Congress. Washington, a former officer in the French and Indian War, was not initially a popular choice among some of the delegates, who favored military veterans with more combat experience. However, Washington was an ideal choice for other reasons: he was from Virginia, which gave the Continental Army a strong representation from the South, and he was a respected leader with a reputation for integrity and calm in crisis.

Washington’s first major challenge was dealing with the British siege of Boston. The city had been under British control since 1768, and when hostilities erupted between the colonists and British troops in April 1775, Boston became a focal point of the revolution. By the time Washington took command, the British had established a firm hold on the city, but the surrounding area was largely controlled by colonial militias.

Washington’s first objective was to break the British siege of Boston and lift the pressure on the Continental Army. The situation was dire—Washington had a poorly equipped army with little formal training, and morale was low. The troops were hungry, freezing, and suffering from diseases like smallpox. Despite these challenges, Washington began to rebuild the army’s organization, discipline, and morale.

In early 1776, Washington’s forces took advantage of their strategic position. They began to fortify the high ground surrounding Boston, particularly Dorchester Heights, which overlooked the British positions in the city. Washington realized that by positioning cannons captured from Fort Ticonderoga on the heights, he could effectively render the British position untenable. He ordered his men to work through the night, dragging the heavy artillery up the hill in secrecy. The operation was risky, but it paid off.

The next morning, when the British soldiers looked out from their positions, they saw the Continental Army’s cannons pointing directly at them. The British, realizing that their control of Boston was now in jeopardy, had no choice but to evacuate. On March 17, 1776, the British withdrew from Boston, and Washington’s first major victory was secured. This victory, while not a decisive blow in the war, was a huge morale boost for the colonists and cemented Washington’s status as a capable and decisive leader.

The British withdrawal from Boston marked the end of the siege and was a critical moment in the early stages of the Revolution. Washington’s leadership and strategic thinking had proven successful, and the victory at Boston was a sign of things to come. For the first time, the Continental Army had successfully faced off against the British and emerged victorious, which significantly strengthened the resolve of the colonists to continue the fight for independence.

The Birth of the Declaration of Independence

By 1776, the American colonies were deeply entrenched in their rebellion against British rule. The idea of independence, which had been debated and discussed for years, was now becoming an inevitable reality. Tensions had escalated to the point where it was clear that the colonies would not be able to reconcile with Britain, and calls for independence were growing louder.

The turning point came in early 1776, with the publication of Common Sense, a pamphlet written by Thomas Paine. Paine, a political activist and writer, argued passionately for independence, asserting that it was illogical for a small island to rule a vast continent. His pamphlet resonated with ordinary colonists and intellectuals alike, and it helped galvanize public support for a break with Britain. Paine’s arguments were simple, direct, and compelling, and Common Sense quickly became one of the most widely read and distributed works in the colonies.

With public opinion shifting toward independence, the Second Continental Congress convened again in Philadelphia in the summer of 1776. The delegates, now fully aware that the Revolution had reached a point of no return, began to consider a formal declaration of independence. The task of drafting this declaration was given to Thomas Jefferson, a young lawyer from Virginia known for his eloquence and writing skills. Jefferson, with input from John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and others, crafted a document that would forever change the course of history.

The Declaration of Independence, signed on July 4, 1776, eloquently stated that “all men are created equal” and endowed with “certain unalienable Rights,” including “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” The document laid out the philosophical justification for the colonies’ break with Britain, arguing that governments derive their power from the consent of the governed and that when a government becomes tyrannical, it is the right of the people to overthrow it.

While the Declaration’s lofty principles would inspire generations to come, the document was not just a philosophical treatise—it was a bold and revolutionary act. By signing the Declaration, the colonies were formally committing treason against the British Crown. The British would see it as an act of rebellion, and if the colonies were to lose the war, the signers of the Declaration would be executed as traitors.

The Declaration of Independence was approved by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, and it marked the formal birth of the United States of America. With this document, the colonies declared themselves free from British rule, and the war for independence entered a new, more serious phase. The signing of the Declaration did not immediately end the war, but it shifted the nature of the conflict from a rebellion to a full-scale struggle for sovereignty and self-determination.

The War Continues: From New York to the Winter of 1776

After the Declaration of Independence was signed, the war took on a new intensity. No longer fighting merely for better treatment or for the repeal of specific taxes, the colonists were now fighting for their complete independence from Britain. The British, too, saw the war in a different light. What had begun as a rebellion against taxes was now an outright revolt that threatened the very foundation of the British Empire.

In the summer and fall of 1776, the British launched a series of attacks aimed at crushing the rebellious colonies. Their first major target was New York, a critical city that was not only an economic hub but also strategically located between the northern and southern colonies. The British hoped that by capturing New York, they could split the colonies in two and isolate New England, the heart of the rebellion.

The British landed in Staten Island in late August 1776, and General William Howe led his forces against the Continental Army, which was commanded by George Washington. Washington, with a force of around 20,000 soldiers, faced a much larger and better-equipped British force of over 30,000 men. Despite his best efforts, Washington was unable to hold New York, and the British captured the city by early September.

The loss of New York was a major blow to the American cause, but Washington’s leadership remained resolute. His army was badly defeated, but he managed to avoid complete destruction, conducting a series of retreats that eventually took his forces across New Jersey into Pennsylvania. The British, confident that they had won a decisive victory, did not immediately press the advantage. They set up camp in New York and awaited reinforcements, allowing Washington and his men to regroup.

By the time winter arrived in late 1776, the Continental Army had suffered a series of defeats. Washington’s forces were cold, hungry, and demoralized, with many soldiers abandoning the army. Washington’s leadership was called into question, and the future of the Revolution seemed uncertain. However, the general refused to give up. He knew that the war was not lost yet, and that the colonists’ spirit remained strong despite the setbacks.

In late December 1776, Washington launched a daring and unexpected attack against the Hessian forces in Trenton, New Jersey, after crossing the icy Delaware River. The surprise attack was a stunning success, with nearly 1,000 Hessian soldiers taken prisoner. The victory at Trenton provided a much-needed morale boost for the Continental Army and helped Washington regain the confidence of his troops and the colonists. Though the war was far from over, the victory at Trenton was a critical turning point in the struggle for independence.

Conclusion

The American Revolution was not just a fight for independence; it was a struggle for a new identity, one founded on the principles of liberty, equality, and self-governance. From the early skirmishes in Lexington and Concord to the bold Declaration of Independence, the colonies demonstrated unwavering determination to break free from British rule. Each pivotal moment—from the capture of Fort Ticonderoga to the Siege of Boston—played a crucial role in shaping the course of the revolution. Despite the many hardships faced by the Continental Army, the vision of freedom kept the colonists united. The Revolution was more than a military conflict; it was a fight for the future of a nation, one that would come to embody the ideals of democracy and the pursuit of happiness. Though the road to independence was long and fraught with challenges, the American Revolution ultimately forged a new nation that would inspire the world for centuries to come.

This article covers events leading up to the Declaration of Independence in 1776. To read about what happened next, check out American Revolution: The Birth of a Nation.