China and India, two of the most populous countries on Earth, are home to nearly 2.6 billion people, over a third of the global population. But how did these nations, with their vast and diverse landscapes, come to hold such significant demographic weight? From fertile river valleys to strategic geographical advantages, the history of China and India’s population growth is deeply rooted in their unique environments, agricultural breakthroughs, and political unification. This article delves into the factors that have allowed these nations to sustain large populations for millennia and continue to grow at an extraordinary rate, exploring the geography, agricultural innovation, and historical events that shaped their paths to becoming the world’s most populous nations.

Geographic Advantage: Water, Soil, and Climate

China and India’s geographic locations granted them exceptional natural resources that set the stage for the growth of their massive populations. Access to water, fertile soil, and a favorable climate has long been a requirement for human societies to develop and sustain themselves. Major civilizations throughout history emerged near rivers, lakes, or other natural water sources because these offered irrigation for agriculture, drinking water, transportation routes, and a means for trade and commerce. Without such resources, maintaining large, dense populations would have been impossible.

In the case of China and India, both nations sit within regions that possess all the essential ingredients for robust, long-lasting civilizations. India’s major river systems—such as the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Yamuna—are crucial to the fertility of its land. These rivers are part of the broader Indo-Gangetic Plain, which is one of the most fertile areas on Earth. The annual flooding of the Ganges and its tributaries replenishes the soil with nutrient-rich silt, providing the perfect environment for agriculture. This abundance of water ensured that crops such as rice and wheat could be cultivated in great quantities, which laid the foundation for India’s dense population.

China’s rivers, especially the Yangtze and the Yellow River, also provided critical resources for agriculture and settlement. The Yangtze, being the third-largest river in the world, fed into the vast Sichuan Basin, creating an agricultural powerhouse. Similarly, the Yellow River nourished the North China Plain, which is one of the oldest and most historically significant agricultural regions in China. These rivers offered reliable water sources and, like the rivers in India, made agriculture possible even in regions with less rainfall. China’s natural irrigation systems, reinforced by sophisticated historical projects like the Dujiangyan irrigation system, allowed the population to thrive in these regions, ensuring sustained food production.

Both China and India also benefit from temperate climates suitable for agriculture. These regions are within the Earth’s temperate zones, where moderate seasonal changes support diverse crop cultivation. With stable rainfall patterns and minimal environmental disruption, farming could continue year-round in many regions, further accelerating population growth.

When we look globally, many of the world’s major rivers lie in climates or regions that do not support dense populations. Rivers in harsh climates, such as those in Siberia or the Arctic, offer limited agricultural potential. Similarly, rivers in tropical rainforests are often unreliable for large-scale farming due to the unpredicted nature of rainfall, which hinders consistent agricultural output. The combination of abundant freshwater, fertile soils, and temperate climate zones in China and India created an ideal environment for the rise of large civilizations, laying the groundwork for their massive populations.

Fertile Lands: The Power of Agriculture

The fertile plains of China and India have long been essential to their population growth. Agriculture is the cornerstone of civilization, and it is through farming that societies generate the resources necessary to support large numbers of people. China and India’s fertile lands, particularly in the plains surrounding their major rivers, allowed for the large-scale cultivation of staple crops, which in turn sustained vast populations.

India’s Indo-Gangetic Plain is one of the most productive agricultural regions in the world. It stretches across much of northern India, from the eastern to the western borders, and has been the cradle of civilization for millennia. This fertile area benefits from alluvial soil deposited by the Ganges, Yamuna, and other rivers, making it highly suitable for rice, wheat, and other crops. Rice, in particular, has been a fundamental crop in the region due to its high caloric yield per hectare, which allowed for the feeding of large populations. India is one of the largest rice producers in the world, and the crop remains central to its economy and food security. The labor-intensive nature of rice farming also meant that larger families were required to tend to the fields, creating a cultural and economic incentive for having more children, which further propelled population growth.

In China, the Yangtze River Basin and the Yellow River Valley have similarly rich soils. These two regions provide a steady food supply through rice cultivation in the south and wheat cultivation in the north. The Yangtze, with its sprawling, fertile basin, produces some of the best rice paddies in the world, while the Yellow River Valley, one of the cradles of Chinese civilization, is ideal for wheat and millet farming. These regions have supported dense populations for thousands of years. The abundance of food in these areas allowed for food surpluses, which not only sustained large populations but also supported urbanization and the rise of complex societies.

Beyond rice and wheat, both China and India have benefited from a variety of crops suited to their respective climates. India has cultivated sugarcane, cotton, and a vast array of spices, while China has traditionally grown tea, soybeans, and numerous vegetables. Both nations have also utilized extensive irrigation networks, such as China’s canal systems and India’s traditional water management methods, to ensure stable agricultural output even in dry periods.

With agriculture being the backbone of their economies, both nations also benefitted from extensive trade networks that allowed for the exchange of goods and agricultural products. Ancient trade routes, such as the Silk Road for China and maritime trade networks for India, facilitated the spread of not only commodities but also agricultural techniques and crop varieties. This trade helped bolster agricultural output and improve food security, which in turn supported further population growth.

The sheer scale of agricultural production in both India and China is a critical factor in their population growth. These nations are home to some of the most fertile and productive agricultural lands in the world. Their ability to consistently produce food on a massive scale meant that both nations could support increasingly larger populations, even as they transitioned into more urbanized, industrialized societies.

Natural Defenses and Geographic Isolation

While fertile lands and favorable climates played a critical role in the development of China and India’s large populations, another significant factor was the geographic isolation and natural defenses these regions possessed. Both countries were protected by imposing physical barriers that not only safeguarded their resources but also reduced the frequency and intensity of external invasions. This relative isolation allowed the civilizations within China and India to grow and develop with fewer interruptions from external forces.

India’s northern border is protected by the Himalayan mountain range, which forms a natural barrier against invasions from Central Asia. These formidable mountains have historically made it difficult for enemy forces to penetrate India from the north. To the west, the Thar Desert and the Indus River further serve as natural obstacles, providing another line of defense against external threats. To the east, the dense jungles of Southeast Asia made it difficult for invaders to gain a foothold. These natural barriers, combined with the strategic positioning of the Indian subcontinent, helped protect India from the constant invasions that plagued other parts of the world. This allowed India to remain relatively secure and focused on internal development, agriculture, and population growth.

China, likewise, benefited from its natural defenses. The vast Siberian tundra to the north provided an inhospitable environment for invasion, while the Gobi Desert to the west and the Tibetan Plateau to the south formed additional protective barriers. The Pacific Ocean to the east created an additional natural defense that helped insulate China from naval invasions. These geographical features made China a challenging target for invaders, allowing it to focus on internal development, which in turn contributed to its population growth.

While no natural defense is entirely foolproof, these geographical advantages significantly reduced the frequency of invasions, which helped maintain the stability of both China and India. The natural borders provided a buffer that allowed both nations to grow their populations without the constant disruption caused by external conflicts. Over time, China and India became centralized, powerful civilizations, capable of withstanding external threats and focusing on the internal processes necessary for sustained population growth.

This geographic protection also enabled both countries to develop internal trade networks, making it easier to move goods and resources within their borders. The absence of constant warfare meant that resources could be channeled into infrastructure, agriculture, and urbanization, further fueling population growth.

In conclusion, the natural defenses of China and India, combined with their favorable geographic locations, helped shield both nations from the waves of invasion that devastated other regions. This protection, in turn, allowed these nations to build and maintain large, stable populations over the course of their histories.

Historical Advantage: Early Agricultural Societies

One of the key factors that set China and India apart from many other regions in terms of population growth is the early development of agricultural societies. Both countries transitioned to settled farming societies thousands of years ago, which provided them with a crucial head start in building large, complex civilizations.

Agriculture, as the backbone of human society, allowed both China and India to support much larger populations than nomadic or hunter-gatherer societies could. The transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture marked a fundamental shift in human history, enabling communities to build permanent settlements, invest in infrastructure, and engage in trade. Early agricultural societies had access to surplus food, which enabled population growth, facilitated the development of cities, and allowed for specialization in other areas of life, such as craftsmanship, writing, and governance.

Both China and India made their agricultural breakthroughs around 8000-9000 BC, long before many other civilizations in the world. This early transition to agriculture helped these two regions sustain large, growing populations. In China, the ancient civilizations of the Yellow River Valley are among the earliest examples of agricultural societies. The fertile soil along the Yellow River supported the growth of wheat, millet, and rice, which provided the food necessary to support larger communities. The introduction of irrigation allowed the Chinese to increase crop yields, contributing to population growth.

India, too, developed early agricultural practices, particularly along the Indus River, in the area now known as the Indus Valley Civilization. This region, characterized by rich alluvial soil, was ideal for growing barley, wheat, and legumes. The agricultural output of the Indus Valley helped sustain large urban centers like Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa. The surplus of food allowed for a growing population and the flourishing of trade, culture, and technology.

The ability to produce surplus food created economic stability in both regions. For example, early civilizations like the Indus Valley and those along the Yellow River did not need to worry about their immediate food supply, unlike other ancient cultures that were vulnerable to crop failure or famine. The stable food supply enabled them to focus on other areas of development, such as the arts, architecture, and governance. Over time, the ability to produce food surpluses would become one of the main driving forces behind the growth of China and India’s populations.

Unification and Population Growth

The historical unification of China and India played a significant role in the growth of their populations. Early political consolidation allowed both countries to stabilize and manage their vast territories and resources more effectively, which directly impacted their ability to sustain large, growing populations. By unifying their diverse regions under single rulers, both India and China were able to create more centralized governments, improve infrastructure, and promote economic development, all of which helped foster population growth.

In India, the Maurya Empire, under the leadership of Emperor Ashoka, was one of the first major unifications. Ashoka’s reign in the 3rd century BCE marked the peak of India’s territorial unification. Under his leadership, the empire expanded to encompass most of the Indian subcontinent, from the northwest to the southeast. Ashoka’s efforts to spread Buddhism and promote social welfare policies, alongside a strong administrative structure, helped solidify the empire’s control and created a more stable environment for population growth. The consolidation of power allowed for the efficient distribution of resources, better trade networks, and greater unity among the people, all of which helped India support its growing population.

In China, unification came earlier, under the Qin Dynasty in 221 BC. The Qin Dynasty marked the first time that China was unified into a single empire, following centuries of fragmented rule by various warring states. The first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, centralized power, standardized weights and measures, and connected the various regions through roads and canals. His policies facilitated the movement of goods and people, which helped boost trade and agricultural production across the empire. The construction of the Great Wall of China and other defensive infrastructure also played a role in protecting the empire from external threats, allowing the population to grow without the constant fear of invasion.

Unification in both China and India allowed for the efficient administration of large, diverse territories. With centralized governments, these countries were able to implement agricultural reforms, build roads and infrastructure, and foster trade networks that connected rural areas with urban centers. This increased access to resources and promoted stability, which in turn supported the expansion of their populations. The unification of both regions allowed for a greater sense of national identity, and the stability provided by centralized rule enabled both India and China to continue to grow demographically.

Population Explosion in Modern Times

The 19th and 20th centuries saw both China and India experience unprecedented population growth, driven by industrialization, medical advancements, and agricultural improvements. While many parts of the world saw their populations stabilize or even decline during this time, China and India’s populations skyrocketed as their economies and societies modernized.

In the case of China, the population grew from approximately 430 million in 1850 to over 1.3 billion by the 21st century. This growth can be attributed to several key factors. The industrial revolution in China, which began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, helped create more job opportunities, boost agricultural output, and improve living standards. Additionally, improvements in public health, such as the introduction of vaccines, better sanitation, and advancements in medical care, significantly reduced mortality rates and allowed the population to grow. As food production became more efficient, particularly through the use of modern irrigation systems and farming techniques, China’s population was able to expand rapidly.

However, China also faced challenges in controlling its rapid population growth. During the leadership of Mao Zedong, the government encouraged large families as part of a broader social and economic strategy. The result was a population boom in the mid-20th century. By the time the Chinese government realized the strain this population growth was placing on resources and infrastructure, it was too late. In 1978, after Mao’s death, China instituted the one-child policy, which was meant to curb the population growth and ensure that the country could continue to develop its economy without overtaxing its resources. While this policy did reduce birth rates, China’s population continued to grow due to the sheer size of its base population.

India, on the other hand, saw its population grow from 125 million in 1750 to 389 million by 1941. By the 21st century, the population of India, including Pakistan and Bangladesh, surpassed 1.6 billion. Unlike China, India did not implement a single-child policy but instead continued to experience high birth rates due to its cultural values around family size. India’s population explosion in the 20th century was driven by similar factors as China’s: advances in medicine, agriculture, and infrastructure. The Green Revolution in the 1960s, for example, introduced high-yield crop varieties and modern farming techniques that greatly increased food production, reducing famine and helping sustain a rapidly growing population.

Despite attempts to introduce family planning programs in India, such as the forced sterilization campaigns in the 1970s, resistance to such measures remained high in certain regions, particularly due to cultural preferences for large families. While birth rates have declined in recent years, India’s population continues to grow, albeit at a slower pace. Today, India’s population growth has been impacted by urbanization, improved education, and greater access to healthcare.

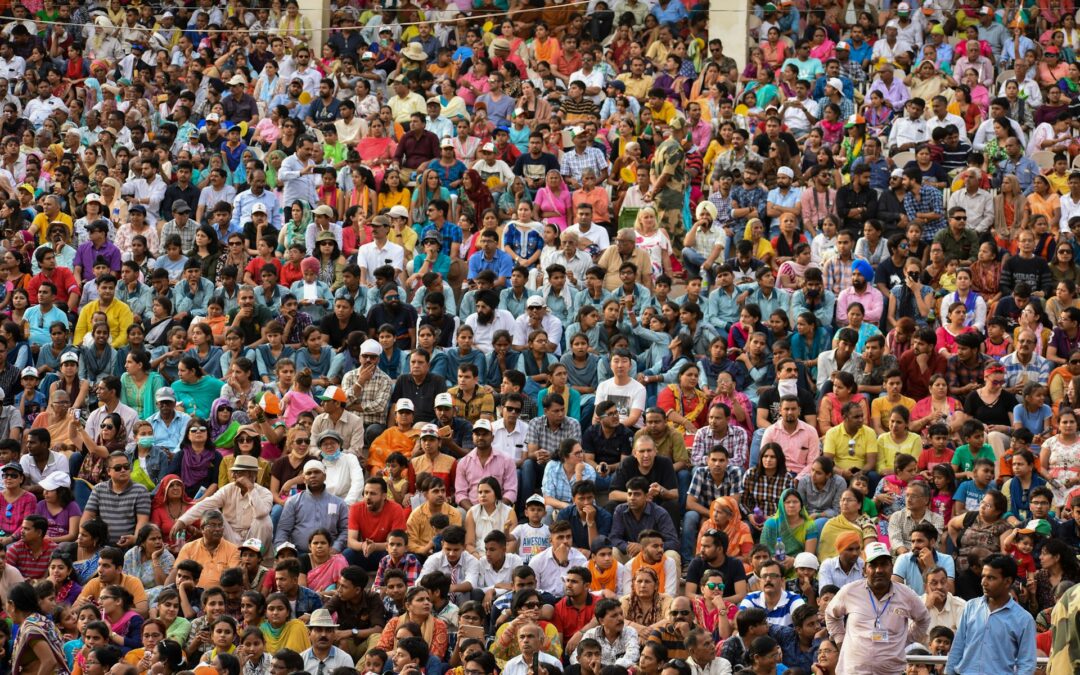

Both China and India’s massive population growth has created complex social, economic, and environmental challenges. Urbanization has led to the growth of megacities, while pressure on resources such as water and energy has escalated. The sheer scale of their populations has made both countries central players in global economics, politics, and culture, influencing everything from global supply chains to environmental policy. The rapid population growth, fueled by a combination of early agricultural development, unification, and modern advancements, has allowed China and India to become two of the largest and most influential countries in the world today.

Conclusion: Strategic Geography and Cultural Legacy

The massive populations of China and India are a result of their strategic geographic locations, abundant natural resources, favorable climates, and long histories of agricultural development. These factors allowed both nations to grow and sustain large populations, which helped shape their civilizations into what they are today. Their histories are also marked by unification and stability, which further supported population growth.

While other regions faced significant setbacks, such as plagues and wars, China and India were able to maintain relatively stable growth, allowing them to become the most populous nations on Earth. Their unique geographical and historical advantages, along with their capacity for large-scale agriculture, set the stage for a population explosion that continues to shape the world today.